The Press and War: Watchdog, Lapdog, or Guide Dog?

How often have western media actually questioned their country's war efforts before hostilities begin?

Note: The piece below is a brief interlude from our regular coverage. More on our usual topics is in the works and should be coming soon.

Three newspapers are more to be feared than 100,000 bayonets” — Napoleon Bonaparte(?) 1

This article was spurred on while listening to the latest All-In Podcast episode. As the participants discussed US strikes on the Houthis and the movie Wag the Dog, I started thinking about the relationship between the media and war. So in the spirit of Do Your Own Research… here we go.

As context, I studied journalism some 20 years ago now. In my mind growing up, and for a long time, the idea of a journalist would conjure up a left-leaning bespectacled intellectual, drowning in books, infinitely knowledgeable about history, taking the establishment to account and absolutely, fiercely adverse to war.

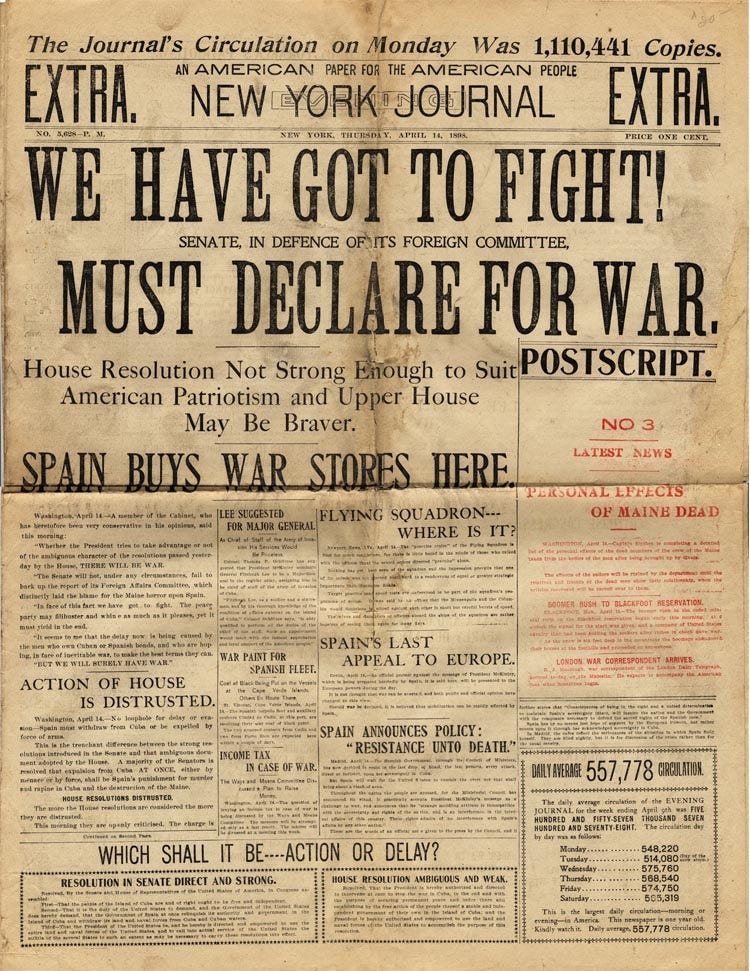

Yet… what is the reality? Reflecting on major conflicts from recent and less recent times, I could instantly think of several that were heartily cheered on — and possibly enabled — by the media. Take the 1898 Spanish American war or the 2003 US invasion of Iraq.

The Vietnam war is the most obvious counter-example. Yet it’s not as clear cut as one might think. It’s well known that the media turned against the war after the conflict had been going on for a while and reporters started bringing back the horrors of the war such as the burning of Can Me in August 1965 to people’s living rooms. What was their stance at the start of the war, however? While US involvement really escalated in the early 1960s and exploded in 1965, it actually started in 1955. Small snippets I could find (such this educational resource) describe initial coverage as “generally positive and upbeat”, but without citing references. Britannica, also without giving a reference (argh), writes: “many experts who have studied the role of the media have concluded that prior to 1968 most reporting was actually supportive of the U.S. effort in Vietnam.”

In other words if you take the start of the war as meaning 1955, coverage was likely initially supportive. If you consider that it was closer to 1964, which is when it really became real for most Americans, the answer is less straightforward.

So the question remains: Are there contemporary examples where a Western country went to war, with the majority of its own media questioning the decision?

Take the Iraq invasion of 2003 — one I am most familiar with, as I was in the UK at the time and had joined the Feb 15 million-strong anti-war protest (so much for that). Mainstream newspapers and cable channels overwhelmingly supported the UK involvement, with a few notable exceptions, the Daily Mirror, The Independent and Channel 4 (see here and here). In the US it was even more extreme, with all the large media channels and papers rallying behind the war effort. Dissenters like The Knight Ridder Washington bureau (owners of Philadelphia Inquirer) couldn’t make a dent against these.

Researching around, one potential counter-example I could find was the Suez crisis of 1956. While The Times, Express and Daily Telegraph initially expressed support for decisive action against Nasser's move to nationalize the Suez Canal, the intervention was opposed by the Guardian (then the Manchester Guardian), questioned by The Daily Mirror, The Economist and the New Statesman. Even the BBC, it seems, only towed the line under significant pressure and censorship by the government. (That same article notes the government even considered installing permanent broadcasting facilities at N° 10 Downing Street (!) later that year).

Even so, according to this journal article (The British Press In The Suez Crisis): “the press, in its overwhelming majority, was in favour of a very strong response to Nasser. A small group of newspapers was advising caution, following Sir Anthony's watchword 'Firmness, with care', whereas an even smaller portion of the press was opposed at all costs to any forceful action against Egypt.”

What follows is a summary of what I could find about the media in some of the major conflicts of recent times. As a caveat, this focuses mainly on the UK and the US, and for time reasons, I didn’t cover them all.

The Spanish-American War (1898): Known as the first media war, the new and influential yellow press in the United States at the time beat the drums of war so loud, that it has even been said it caused the war. Many will be familiar with William Randolph Hearst’s (possibly fake) quote “You furnish the pictures, I’ll provide the war!” The US Library of Congress itself writes Congress declared war under pressure by the yellow press. Others such as this article by History acknowledge the role of the press in intensifying hostilities but deny that it actually caused a war. 2

World War I (1914-1918): From memory of history classes, WWI was cheered on by the European presses. But it wasn’t completely uniform. In the UK for example, the Guardian (then called The Manchester Guardian), had actually been warning against British involvement in a war. Prior to the war in fact most UK newspapers had stayed neutral and avoided calling for British action. However, they all rallied behind the effort once war broke out.

The Algerian War (1954-1962): This is an interesting one. According to this detailed essay (in French), the press initially largely went along with the government’s minimization of the conflict, to the point of acting as if no war was happening and not paying it much heed. The conflict — considered as perhaps the bloodiest and most violent of the wars of decolonization — did seemingly not make a big dent on the frontpages til 1956, at which point dissent in the media and public opinion did start emerging.

The Suez Crisis (1956): As described above, this is perhaps the clearest case I found of substantial media opposition to a government intervention.

World War II (1939-1945): I’ll focus on the UK here again. This article in the Journal of Contemporary History argues the press was under the tight grip of the government, and therefore largely fell in line with Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policy. According to the article, “Chamberlain has been called the 'first prime minister to employ news management on a grand scale’”. However, the media didn’t question or oppose the country’s entrance into the war, neither. (For a most entertaining read on the government’s censorship at the start of the war, and ensuing chaos, I recommend this read here - someone should make a movie out of this).

US-Korean War (1950-1953): I cannot find too much about this, but the impression I’m getting, from for example this article, is that a) the war didn’t initially get much coverage and b) the coverage it did get was largely non critical. Very soon, censorship played a role — as detailed in this article in the Australasian Journal of American Studies, with examples as early as July 1950, shortly after the US had sent troops.

Vietnam War (1960s-1975): As written above - if one considers the war as starting in 1955, coverage was reportedly initially supportive. If one considers that it was closer to 1964, the answer is less straightforward.

Falklands War (1982): This was an undeclared war, where the UK responded to an attack by Argentina. The UK media is known to have been highly patriotic during the campaign, as illustrated by the Sun’s Gotcha! frontpage. This article has some insight into the press’s attitude during the events leading up to the war in April, but doesn’t tell us of any clear opposition or support.

Gulf War (1990-1991): In the US, the media appears to have overwhelmingly supported the US-led attack against Iraq. In “Operation Desert Cloud: The Media and the Gulf War”, Marie Gottschalk writes: “A survey of the editorial pages of five of the country's newspapers before and during the war found that editorials ‘refused to wander beyond the parameters of the discussion as it unfolded in Washington; while they differed in tone and degree, they display considerable consensus in their views of the Middle East, its people, and the interests of the United States in the region.’ Another survey, this one of the country's 25 largest newspapers from the start of the invasion in August until mid-November, found that only one - Colorado's Mountain News- argued for the most part against military action as a last resort to get Iraq out of Kuwait.” The rest of the article is a fascinating read on how the media swallowed the official line lock stop and barrel during the conflict.

NATO bombing of Yugoslavia (1999): This is a unusual one as the attack was carried out by an international organization. The US was a major actor and proponent though. Again it appears the US media were generally supportive of NATO's intervention, going along with framing it as a humanitarian effort. In The Kosovo War In Media, Festim Rizanaj writes: “Daya Kishnu Thussu argues that NATO’s precedent-setting action (…) was reported uncritically and presented by CNN as a humanitarian intervention. Television pictures tended to follow the news agenda set up by the US military. Few alternative views were aired and, most importantly, a fundamental change in the nature of NATO — from a defence alliance to an offensive peace-enforcing organization — was largely ignored (Thussu, 2000: 345).”

US-led invasion of Afghanistan (2001-2014): Following the 9/11 attacks, there was significant popular support in the US for an attack on Afghanistan. According to Timothy McCarthy, adjunct lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School, the media failed to critically question the justification and rationale for the war. In Framing The War On Terror, the authors likewise describe how journalists internalized the government narrative about the war on terror, without much questioning: “In addition to simply repeating the preferred terminology of the President, journalists reified the policy – treating it as an uncontested ‘thing’ – and naturalized it, suggesting they accepted its use as a way of describing a prevailing condition of modern life.”

Iraq War (2003-2011): As described above, all the significant US media rallied behind the war effort, with a few dissenters like The Knight Ridder Washington bureau. In the UK, the picture was more nuanced but again overwhelmingly in favor of the invasion.

Libya Conflict (Mar-Oct 2011): This brilliant research article by Maggie Moore — with a perfect title you might recognize: Watchdog or Lapdog? — examines the role of the US media in the Libyan intervention. How did Obama’s response go from “gravely concerned” on Feb 21, 2011, to “We cannot stand idly by” a month later, she asks? Her findings are fascinating, and show that the US media in that period was more belligerent than the Obama administration, which was trying to stay out of the Middle East. “Describing Obama’s desire for consensus as ‘prudence to the point of procrastination’ editorials pleaded for action before it was too late to be of assistance,” she writes. I find this even more noteworthy when one considers that the US public itself had no appetite for intervening in Libya, at least according to this Pew Research poll taken only 5 days before the US started the bombing.

What sells a newspaper? ‘War’

Of course there’s a vicious circle here as in times conflict escalation, governments will pull out all the stops to extinguish opposition. Several of the sources referenced above describe far reaching censorship operations in place in times of war.

In the words of retired U.S. Navy Adm. James Stavridis, reflecting on lessons from the Ukraine war: “we must engage and win the information war… This means dominating the news cycle, producing compelling visual content (think TikTok-style video) and putting forward competent, believable spokesmen.”

“Mass media do less to mirror the world as it is than to shape a world as it should not be” — Ajai K. Rai

But the media, it seems, doesn’t always need to be forced to do the government’s bidding. And not without reason. To quote a former associate of Lord Northcliffe (a UK newspaper magnate and government director of propaganda in 1918):

‘What sells a newspaper?’ A former associate of Lord Northcliffe answers: “The first answer is "war.” War not only creates a supply of news but a demand for it. So deep-rooted is the fascination in war and all things appertaining to it that . . . a paper has only to be able to put up on its placard ‘A Great Battle’ for its sales to mount up."

In an article in Strategic Analysis, Ajai K. Rai writes that during the Gulf War, 20 of the US’s 25 most read newspapers had higher circulation, while CNN got a ten-fold audience boost. In 2003, Variety reported that coverage of the Iraq war had benefited all US cable channels, led by a 45% primetime news boost for Fox News. More recently Yahoo reported that views jumped 22% and 13% respectively for Fox and CNN in the week following the Oct. 7 attack in Israel. From the same article:

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, primetime viewership for all three major cable news networks climbed 49.9% from the previous week. In the first week of the Ukraine war, CNN averaged 1.496 million primetime viewers, 161% more than its 573,000 average the previous week.

161% boost! Fancy that.

So perhaps it is no surprise that the media itself will track down and silence war critics. Quoting Rai in Strategic Analysis again:

(…) sections of the media also sometimes prove eager to discipline dissident voices within their own profession. Condemnation of those 'traitors' attempting to dispel the 'fog of falsehood' is not enacted by the state alone, but often by rival media who shoulder up squarely with government and military, branding as unpatriotic any outlet which sets broader limits on the expression of critical, or merely sceptical, viewpoints. John Simpson, for example, noted with dismay during the Gulf War that many of his colleagues demanded a curb on free reporting.

Rai adds, later on: “Likewise, some American print journalists were the harshest critic of CNN's reporting from Iraq, and of what they perceived as unacceptable 'neutralism' in television coverage.”

So where does this leave us? From the examples I looked into, the media has a pretty poor track record of resisting calls for war. Too often, it swallows the initial official narrative whole and toes the line, aided by varying degrees of censorship and coercion. In some cases it might even be the more belligerent actor. So as the WSJ welcomes the US bombing the Houthis “at last”, as Politico calls for more assertive action by Biden against Iran (but not without first massaging public opinion, mind you!), as a Fox News opinion piece calls for Biden to invoke the Reagan doctrine against Iran, it’s worth keeping in mind who is really whispering behind the scenes.

To take with a grain of salt. The English citation I’ve seen goes like this: “Four hostile newspapers are more to be feared than a thousand bayonets”. It props up in multiple places online, including Wikipedia, without any reference as to its origins. In French, the citation is slightly different (3 newspapers, 100,000 bayonets). It’s quoted in multiple places online but trying to track down the source of the quote, the only reference I could locate is this magazine article from 2004, by Anne Bernet. The article isn’t available online but for whatever reason, an eBay listing has photographs of the article pages, and page 63 shows the citation as a pull quote. But there is no reference as to the source.

Yet, China can fly spy balloons over the US without consequence. How does that fit into the historical list?

Great article. I remember most all media in my lifetime cheerleading for war before and after the start. Of each war.

There are so many wars to choose from.

You left out Grenada under Reagan where the USA treated the Cuban Embassy like the Iranian Students treated the USA embassy after Jimmy Carter welcomed his Dictatorship of the Royalty Pal the Shah of Iran into the USA.

As I recall most everyone cheered. Yeah sure the Challenger blew up killing everyone aboard but we Conquered a Dagger Pointed At The Heart of America called Grenada.

(Before the Blitzkrieg..Pearl Harbor type attack....I remember Maurice Bishop on this public TV show...was it Charlie something???? Talking about how I think George Schultz was demonizing Maurice Bishop and Grenada....and how as head of state of Grenada in the United States he could not even get a meeting with anyone in the USA state department.)

And during the Bush the Elder war on Iraq over Kuwait I recall Media pro war and self riotous about one country cannot take another country's territory by force.....ignoring that that year the USA gave Israel Billions of Tax Dollars to ESTABLISH RELIGION in "the "Occupied Territories"( why was it wrong in Kuwait but right in Israel....right in Morocco and Sahara dessert and wrong in Kuwait??? Never crossed our wars cheerleading Media minds...

☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆

It seems even worse these days though it seems people now get the world news from whoever they follow and whatever their algorithm feeds them???

☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆☆

I'm new to Substack...if anyone wants to help me get writing career off the ground I have a GoFundMe and will have paid subscriptions soon I hope.

https://www.gofundme.com/f/my-puppy-wants-a-cheeseburger