Did Use Of Ivermectin In Latin America Sabotage Clinical Trials and Confuse The World Of Medicine?

In late 2020, a curious article from Nature Magazine made the rounds:

Its chief concern? That people in Latin America were taking ivermectin as a COVID-19 treatment, and therefore local studies were very hard to execute:

Some early studies in cells and humans hinted that the drug has antiviral properties, but since then, clinical trials in Latin America have struggled to recruit participants because so many are already taking it.

“Of about 10 people who come, I’d say 8 have taken ivermectin and cannot participate in the study,” says Patricia García, a global-health researcher at Cayetano Heredia University in Lima and a former health minister for Peru who is running one of the 40 clinical trials worldwide that are currently testing the drug. “This has been an odyssey.”

Still, researchers might never have sufficient data to justify ivermectin’s use if its widespread administration continues in Latin America. The drug’s popularity “practically cancels” the possibility of carrying out phase III clinical trials, which require thousands of participants — some of whom would be part of a control group and therefore couldn’t receive the drug — to firmly establish safety and efficacy, says Krolewiecki.

As unchecked use of ivermectin grows, he says, “the more difficult it will be to collect the evidence that regulatory agencies need, that we would like to have, and that will get us closer to identifying the real role of this drug.”

What the article says, in brief, is that if a large portion of people in a region are taking ivermectin, it becomes very difficult to create a representative control group for a randomized controlled trial (RCT), since those groups have to not be taking the drug for the trial to have external validity.

The Nature article was published in October 2020—making the case that running large-scale RCTs in Latin America without distorting the results due to community use would be incredibly difficult. Even earlier, in August 2020, headlines like the one below were appearing in the Latin American press:

Despite this obvious red flag, the TOGETHER trial started only a few months after the Nature article, in January 2021. Vallejos started in August 2020, and Lopez-Medina started in mid-July 2020. All three of these trials completed at different times in 2021. These three are arguably the most highlighted trials in the Western press, so it’s worth seeing if there is a common thread that might explain their results.

Meta-analysis

I wondered if perhaps the Latin American use in the community would explain the difference seen between various studies of ivermectin across the world. To avoid study selection effects, I used the exact same studies used in the JAMA paper testing the Strongyloides hypothesis. The only update I’ve made is to use the final data from the TOGETHER trial. That data was not available at the time of publication of the Strongyloides paper. This is a set of 12 randomized clinical trials reporting all-cause mortality. In many ways, this is arguably the hardest endpoint to game, giving us additional confidence in the results we’re working with.

As you can see, we have a big difference between the two groups: in Latin American studies, we see a very small effect estimate (5%) with no indication of becoming statistically significant. In the trials from every other part of the world, we see a strong reduction of mortality (55%), with statistical significance. The difference between the two groups is also statistically significant, with p=0.03.

To be clear, this doesn’t necessarily mean that background use is explanatory of the results. All we see is that there is significant correlation between the location of the trial being in Latin America or not with whether it showed a strong signal of ivermectin working. It could well be that other Latin America-specific reasons, such as the P.1/Gamma variant, or perhaps the interaction between local political and academic culture interfering with the results of these clinical trials.

For this reason among many others, we can’t be satisfied just with a statistical test. That only tells us there’s a signal worth exploring. We should try to see what more we can learn by checking the situation on the ground, looking at each study separately.

Let’s Google It

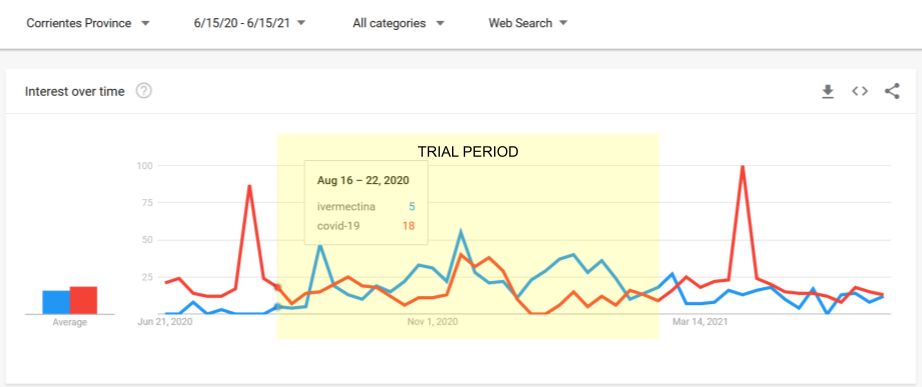

In an attempt to gather somewhat untainted data that may help to answer this question, I used Google Trends to see what the search traffic for ivermectin was at the time and region where each trial took place. Since Google Trends does not offer absolute counts—but only comparisons—I compared searches in each area with searches for COVID-19, which we would expect to form a suitable baseline. In countries where the main language is not English, I also included non-English keywords in the local language, especially where they had meaningful traffic.

For example, this is what the trend looks like for TOGETHER:

About a month before the start of the trial, ivermectin use had its first peak, exceeding the search traffic to “covid-19” for 5 continuous weeks, with sustained search traffic afterwards. The second peak is on the week where the ivermectin arm restarted with a higher dose.

The metric I wanted to calculate was the ratio between “ivermectin” searches and “COVID-19” searches. In the case of TOGETHER, over the course of the study’s run, ivermectin searches come up to 54% those of the “COVID-19” keyword.

Looking at all the studies through the same lens, the conclusion was pretty stark: of the studies in Latin America, only in Beltran-Gonzalez has ivermectin searches that are below 50% of COVID-19 searches. In the non-LatAm group, no study or study location exceeds 42%.

You can see the charts for the individual studies below (or larger in the appendix):

Investigator Statements

In many of the studies, the investigators were extremely clear that community use was an issue.

Vallejos

The researchers confirm the issue. Here’s a Google-translated pull-quote from an article commenting on the trial:

TOGETHER

The statements of the investigators are many and mutually contradictory. However, the authors of the NEJM publication reporting on the trial, clearly write:

Ivermectin has been used off-label widely since the original in vitro study by Caly et al. describing ivermectin activity against SARS-CoV-2,22 and in Brazil, in particular, the use of ivermectin for the treatment of COVID-19 has been widely promoted.

Lopez-Medina:

As the lead investigator put it in his response:

The need to use D11AX22 rather than ivermectin in the ICF arose from the extensive use of ivermectin in the city of Cali during the study period, extensive recommendations from some political and medical leaders to use it against COVID-19, and the fact that the initial placebo had a different taste from ivermectin.

Note that this had not been mentioned at all in the paper; it was only raised because someone noticed it in an old version of the protocol.

Exclusion Criteria

One way in which trials try to avoid the issue of community use is by asking potential participants if they have taken ivermectin, and excluding them if so. While this may not be successful, since it relies on the honesty of the potential participant, it is the absolute baseline. I was shocked to see the degree to which the Latin American studies did not strictly exclude patients for ivermectin use in the recent past. However, it makes a lot of sense if the investigators feared that this would dwindle their pool of patients down to impractical numbers. Let’s see each of the trials in turn:

Lopez-Medina

While the paper states that the patients needed to not have taken ivermectin for five days in order to be eligible for randomization, in the clinicaltrials.gov pre-registration of the trial, the exclusion criteria didn't say five days: it said 48 hours without ivermectin was enough—in contradiction to what was published.

To make matters worse, the registration was updated after trial enrollment had ended—to agree with the paper—raising serious concerns. People can only see this if they look into the protocol history. Despite intense research into this trial by many others, I’m the first to bring this to light, a year and a half after the trial ended.

TOGETHER

As discussed elsewhere, this topic is complex, especially in the case of TOGETHER. Given that such an exclusion criterion was never written in the trial protocol, even if it was done as the authors of the paper claim, it’s arguably a protocol violation. At the same time, in the limitations section that was later added to the NEJM article summary, the authors wrote:

The authors attempted to screen potential participants for previous ivermectin use.

Obviously, “attempted” and “ensured”—which they use in the main body of the paper—are very different words, with wildly different implications for the trust we can place on this trial. Someone from the trial team must provide additional detail about exactly what was done, but such detail has not been forthcoming.

Beltran-Gonzalez

No mention of exclusion for use of ivermectin in the study protocol.

Galan/Fonseca

The paper mentions the following as an exclusion criterion:

(8) previous use of any of the medications surveyed for more than 24 h

This would presumably mean, similarly to Lopez-Medina, that a single day of abstention would be sufficient to get someone to qualify for being randomized to any of the interventions, which raises incredibly serious questions. In particular, why would the investigators feel the need to define such a tight window, unless they felt that excluding for any recent use would cause them serious inclusion concerns?

Vallejos

This study includes in its published paper the most clear statement of a viable exclusion criterion:

Concomitant use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine or antiviral drugs due to a viral pathology other than COVID-19 at the time of admission was prohibited as was the use of ivermectin up to 7 days before randomization.

It is not clear whether this exclusion was successful, given that they did not perform blood tests on their patients—even as a sample—but nevertheless, this kind of explicit exclusion criterion is a minimum.

Adverse Events Profile

Another way to see if the drug in question is being used in the treatment group—but not in the placebo group—is to see if there is a difference in adverse events in a way that the treatment would cause. For example, here is how the I-TECH study in Malaysia looks in terms of adverse events:

Since diarrhea and dizziness are known adverse events of ivermectin, this gives us evidence that indeed the two groups had a real difference in terms of the treatment regimens they followed.

In the case of the Latin American trials, such differences are hard to find.

Lopez-Medina

When the results of Lopez-Medina came out, the adverse events between placebo and treatment were near-identical, and very very suggestive of ivermectin use.

This list of symptoms, by the way, is described in the study protocol as "symptoms that have historically been reported in subjects receiving ivermectin.” Given the relatively high dose in this trial, it's kinda strange that they appear pretty much evenly across groups.

Galan/Fonseca

No placebo group, minimal detailed information on the adverse events profile.

Vallejos

In the supplementary appendix there is (deleted?) listing of adverse events which shows no real difference between the kinds of adverse events we’d expect to see from use of ivermectin, mostly diarrhea, nausea. Blurred vision, one of the most distinctive side-effects, is not mentioned.

TOGETHER

Gastrointestinal disorders, a typical side effect of taking ivermectin, were substantially higher in the placebo group, raising more questions as to whether the placebo group was getting the benefit of ivermectin use outside the context of the trial.

Beltran-Gonzalez

No mention of any difference in adverse events between the groups, but no further detail provided.

Were the Trials Underpowered?

There are two ways in which the trials could be underpowered as a result of community use of ivermectin. First, the placebo group could end up being a lot less at risk than expected, violating statistical power assumptions. Secondly, patients might be rejected or decline to participate, given that they are already have or are intending to take ivermectin.

So is there evidence that the individual trials were underpowered?

Lopez-Medina:

According to the published paper in JAMA, the investigators were shocked at the degree to which the patients were not degrading:

The primary outcome was originally defined as the time from randomization until worsening by 2 points on the 8-category ordinal scale. According to the literature, approximately 18% of patients were expected to have such an outcome.23 However, before the interim analysis, it became apparent that the pooled event rate of worsening by 2 points was substantially lower than the initial 18% expectation, requiring an unattainable sample size.

To counteract this, they came up with a different endpoint that somehow kept the original recruitment targets identical—though many believe that the new endpoint was just as, if not more, unattainable—and indeed the prediction of how the placebo group would behave was, again, violated in the direction of the trial being underpowered.

Vallejos:

According to the trial’s published paper, yes, and for the same reasons as for Lopez-Medina:

The second is that the IVERCORCOVID19 trial is underpowered because the hospitalization rate was lower than expected when performed in the sample size calculation, as well as the fact that an ambitious reduction of 50–70% was estimated of primary end point.

TOGETHER

Here are some quotes from the principal investigator that indicate the result might have been different if more patients were added:

..the question of whether this study was stopped too early in light of the political ramifications of needing to demonstrate that the efficacy is really unimpressive.. really could be raised. — Frank Harrell,

"I totally agree with Frank — Ed Mills

[vimeo.com].

There is a clear signal that IVM works in COVID patients.. that would be significant if more patients were added.. you will hear me retract previous statements where I had been previously negative — Ed Mills, Together Trial co-principal investigator

Galan/Fonseca

Unclear, no control group to compare to.

Beltran-Gonzalez

According to the published paper, the study was cut short well before the planned 200 patients were recruited:

During the month of August 2020, we observed a very significant decrease in the number of potential candidates that could be included in the study, since practically all hospital admissions required therapy with high oxygen concentrations or invasive mechanical ventilation. Based on the Ethics Committee’s recommendations, we decided to end recruitment and conduct an analysis with the data obtained as of 15 August 2020.

The study’s main weakness is the limited number of patients per group and low

statistical power shown in important outcomes such as death (25%); also, among the pre-established outcomes, we were unable to determine whether the SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests became negative, due to the lack of reactants and the minimal usefulness of proving its negativity from a clinical-practical viewpoint.

Other Evidence

When looking for other signals as to whether ivermectin was used in the community, there is an embarrassment of materials.

Reports at the time of the TOGETHER trial from the local press definitely indicate that ivermectin use was elevated:

In the case of Lopez-Medina, a city-wide program of ivermectin early treatment for COVID-19 was initiated just the week before the Lopez-Medina trial started:

But what about the worms?

I started working on this hypothesis only as a counterpoint to the Strongyloides hypothesis—essentially as a way to show that there are other ways to divide the studies that are just as, if not more, compelling. The results from the initial analysis came up surprisingly strong, and upon deeper investigation, I must say that it now looks to me as a really plausible explanation for what we saw unfold over the last few years.

After correcting an issue with the prevalence estimates, the Strongyloides hypothesis really seems like it’s far less well-supported (p=0.35 for the subgroup analysis and p=0.37 for the meta-regression). In contrast, the “Latin America Community Use” hypothesis presented here has strong subgroup difference (with p=0.03) and given that whether a country is or isn’t in Latin America is pretty set, I don’t expect we’ll need to update our classification soon.

Conclusion

What is certain, is that there was substantial community use in all the Latin American trials, except perhaps for the case of Beltran-Gonzalez. The degree to which each trial managed to exclude patients making such use is up for debate—with some not even showing that an effort was taken, while others went to considerable lengths— such as Vallejos. Regardless, the adverse event profiles, as well as the absence of sufficient statistical power in most of the trials, give us reason to believe that they did not succeed. See the appendix for additional evidence, including local sales data where available.

As such, it is considerably likely that background use in Latin America did indeed skew the results of the trials in a way that created a false negative signal for the world.

What’s more, this pattern highlights an important difference between RCT and observational trials. Patients might be rejected for prior use, or decline to participate in an RCT that only gives them a chance at getting a drug they have over-the-counter access to. And even if they do participate, they may end up taking the drug outside the trial anyway. In an observational trial, where patients are asked if they want to take the drug or not, and they have knowledge of whether they are being given the drug or not, it is much less likely for the patients to cheat, since they have consciously decided to not take it in the first place.

Overall, I am always suspicious of such statistical patterns, so I find it very hard to say that this is or is not what happened. What I can say, however, is that any other hypothesis that tries to explain the efficacy of ivermectin will have to provide evidence that is at least this compelling, if not more.

If you can find any more evidence in favor or against this hypothesis, in relation to any of the Latin American trials—or the ones in the rest of the world—please let me know in the comments. This Substack is called Do Your Own Research, after all, and this hypothesis still has considerable investigating left to do for inquiring minds everywhere.

APPENDIX - Additional Materials

The amount of data I unearthed was too much for the main body of the article, but I did want to make sure I have it all in one place, so this Appendix should serve as a repository for the parts that were left out.

Detailed Google Trends in the Time and Region of Each Trial:

Two weeks after the start of the trial, ivermectin searches spiked and stayed high for the duration of the trial.

About a month before the start of the trial, ivermectin use had its first peak. The second peak is on the week where the ivermectin arm restarted with a higher dose.

A week before the start of the trial, searches for ivermectin peaked. This could be related to a local municipality program that was also distributing ivermectin.

Ivermectin use took off the week after the start of the trial and stayed high for the duration of the trial.

Trial started a week after the initial search interest spike. Some search traffic continued, and the trial ended after the second spike in search traffic during August. Ivermectin community use may not have made a difference here since these patients were late-stage and hospitalized.

What does everywhere else look like?

Here is what the other trial locations look like:

Mahmud (Dhaka), Ravikirti (Bihar), I-TECH (Malaysia), Okumuş (Ankara, Istanbul, Afyonkarahisar), Hashim (Baghdad), Shahbaznejad (Sari), Abd-Elsalam (Assiut, Gharbia)

Hashim is one trial in the non-LatAm group that shows some signal of significant search interest above COVID-19. I’ve also tried to include local alternatives for the search terms of comparison, though they don’t seem to be registering much if any search traffic. The only thing to note is that the search interest seems to be starting long before the trial, and peaks only as the trial stops recruitment, on September 30th.

Ivermectin sales in the time & region of each trial (where available)

TOGETHER:

Lopez-Medina:

Vallejos:

According to TrialSiteNews:

As far as the population in this province, Dr. Carvallo shared that of the total 1,070,283, 26% are under the age of 12. Thus a population of 803,000 inhabitants live here from teenage years and up. Based on drug sales data, Carvallo reported that 668,321 packages of 6-mg pills were purchased at drugstores during the time of the IVERCOVID19 study. As infants, of course, were obviously excluded, Carvallo suggests that much like the study in Cali, Colombia, approximately 80% of the Corrientes population was already receiving ivermectin, either prescribed or self-medicated.

Government Policy:

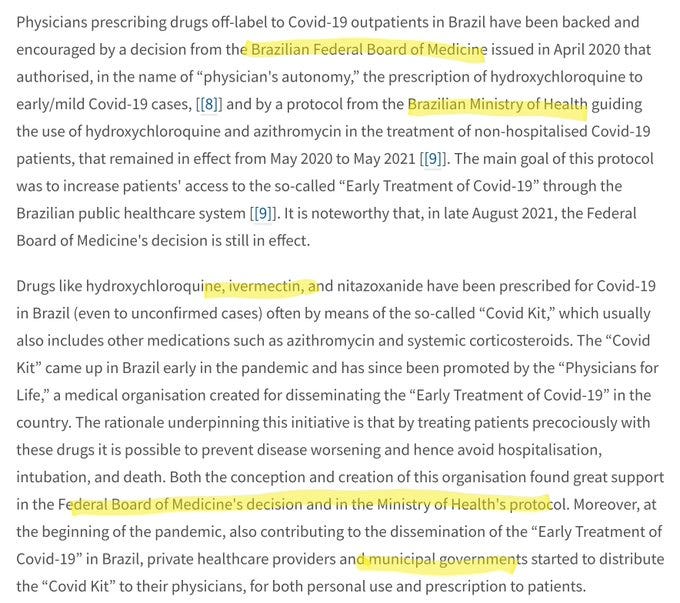

TOGETHER & Galan/Fonseca:

Here’s what a paper in The Lancet has to say about that:

The drug’s popularity “practically cancels” the possibility of carrying out phase III clinical trials, which require thousands of participants —

However it takes just a few mice for a vaccine clinical trial.

Not entirely off topic.

Exclusive: Hindawi and Wiley to retract over 500 papers linked to peer review rings

https://retractionwatch.com/2022/09/28/exclusive-hindawi-and-wiley-to-retract-over-500-papers-linked-to-peer-review-rings/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email