This article is part of a series on the TOGETHER trial. More articles from this series here.

Today, I'll show you one more example of how the TOGETHER trial outputs seem quite willing to blur various boundaries, and always in ways in which help them promote their desired outcome. This particular example is from the fluvoxamine arm of the study.

In a way, you can see this as a demonstration of how tugging at a fairly small thing that looks strange can unearth a whole world of concerning issues about a trial. So let’s see:

Erasing the First Patient

On August 6, 2021, the authors released preliminary results. In them, we were told that:

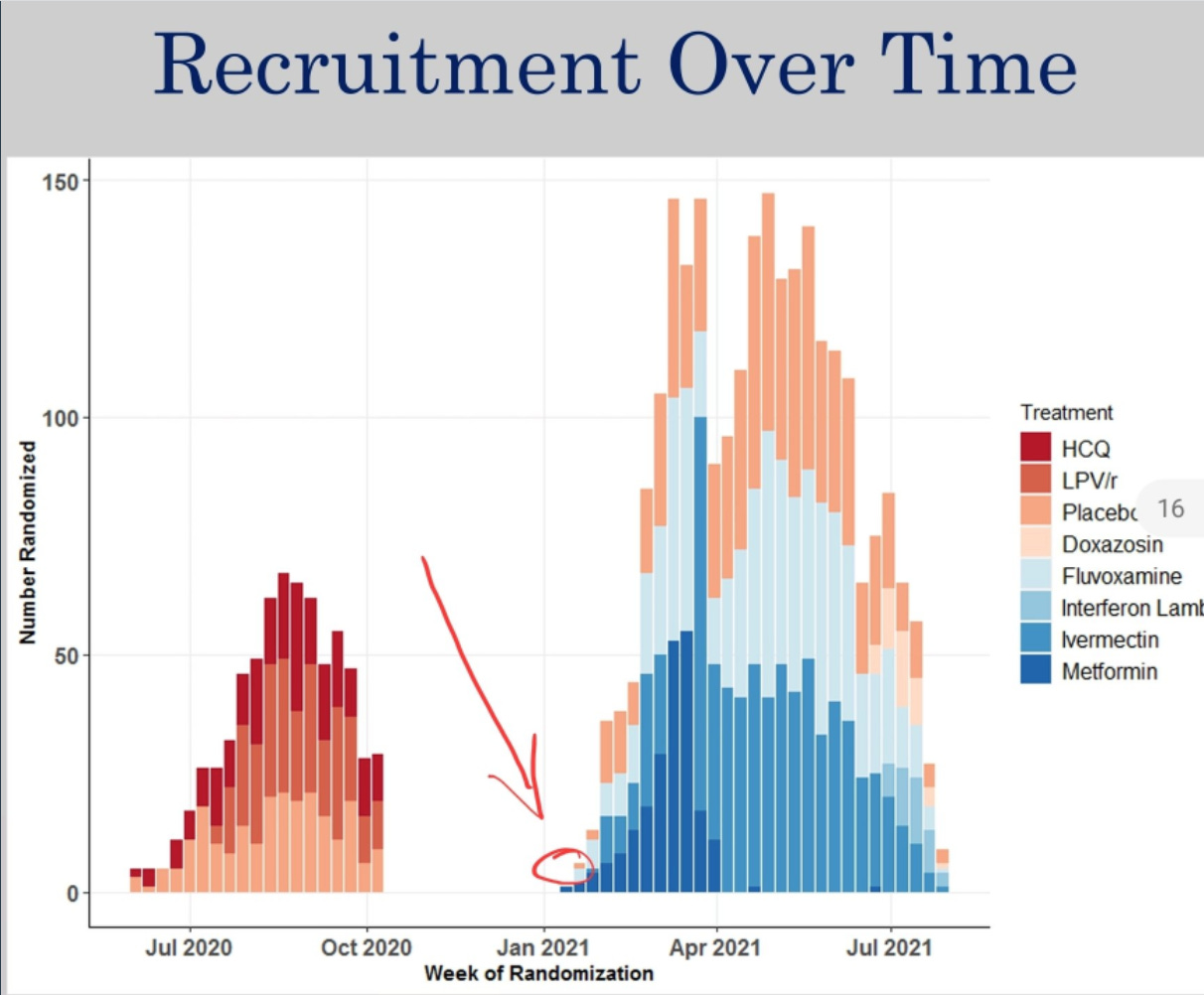

Recruitment started on January 15, 2021.

There were 742 patients in the treatment.

However in the paper published in The Lancet, they say:

Recruitment started on January 20, 2021.

There were 741 patients in the treatment group.

For these statements to be true all at the same time, we would need there to be one patient recruited on or after January 15th, and before January 20th, for them to be included in the August slides, but not in the final paper.

We don't have to wonder about it. If we go back to the August slides, it's right there: three patients recruited to fluvoxamine treatment in the week starting January 18th. One must have been recruited before January 20th.

OK, but this seems excessively petty. Why would they move the starting date just to throw out a single patient?

It’s possible that the patient was randomized on the day the Brazilian ethics board (CONEP) approved their trial, maybe even earlier in the day. The PDF timestamp is actually some time in the middle of that day in Brasilia, so it’s not like they got the approval first thing in the morning.

The Placebo Ghosts

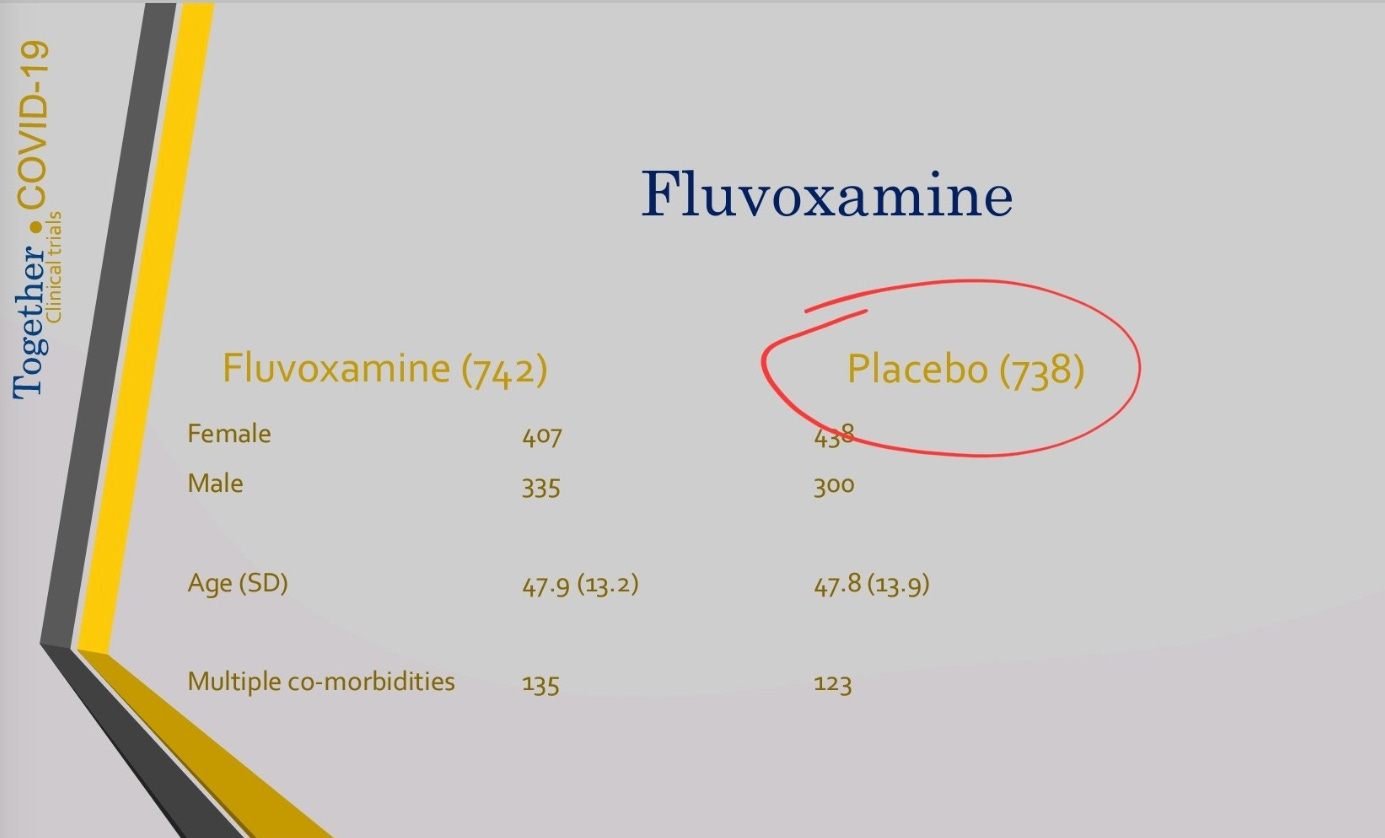

But wait, notice something else: in the August results, there were 738 patients in the placebo group. Yet, the final paper reports 756 in the placebo group. That's not nothing. It's 18 patients, or 2.4% of the placebo group, with the treatment group not increasing at all (or, as we saw, shrinking). Where did those patients come from?

In the August 6th deck, we notice that an interim analysis was done on August 2nd. If deck data is from that review—as it should be—then it looks like they stopped randomizing to fluvoxamine but still used the next 18 patients allocated to the placebo group, until Aug 5th. That’s the obvious hypothesis.

In fact, in the fluvoxamine preprint published a few days later (medrxiv indicates it was approved on August 18th and published on August 23rd), they report 739 treatment patients and 733 placebo patients. And that 28 day follow-up will be completed by August 26th.

The only consistent explanation is that 739 fluvoxamine treatment patients were recruited until July 29th, and another three until August 2nd. But from July 29th until August 5th, 23 placebo patients were added. 1:1:1:1 block randomization is not supposed to create situations where one group grows by three patients while the other grows by 23.

So, once again, we're seeing how the TOGETHER trial either takes liberty with ethics board approvals, then modifies dates to obscure it, or is completely careless with numbers and dates, to the point of self-disqualification. However, it is notable that all the errors we’ve seen so far go towards the same direction of supporting the narrative that the authors clearly are advocating for: fluvoxamine works, ivermectin does not.

Did the Placebo Fudge Matter?

I got some questions on Twitter about what effect the extra 23 patients had on the results of the study. As it turns out, while most of the placebo group was 16% likely to be hospitalized or observed in ER for >6h, for the 23 extra placebo patients it was 48%! Here are my calculations:

As we think about how the extra patients may have affected the results, it is important to note that more events make the placebo group look worse, which is better for fluvoxamine. Let's give it a try:

Version 2 of the fluvoxamine pre-print was posted on August 26, 2021. We can assume it contains a full 28-day follow-up for all the patients mentioned, since they promise exactly this in the paper itself. There, we see that the 733 patients in placebo had 108 events. I assume this is with complete 28-day follow-up.

In the final paper, we see results for all the 756 placebo patients.

And so, you can see that the 23 placebo patients had 11 events (we go from 108 to 119). While the overall placebo group had 16% chances of having an event, this late group had 48% chances of having an event. What???

In the meantime, the two extra patients added to the treatment group had two events. I wonder if things were getting worse in July/August in Brazil (it's the Southern Hemisphere, so that's in the heart of winter).

And of course, you can see the impact this has on the RR credible interval. It goes from 0.71[0.54, 0.93] to 0.68[0.52, 0.88].

So basically, the final effect of fluvoxamine was to reduce risk of $endpoint by 32%, but 3% of that was contributed by the placebo group monkey business—and the interval was shifted off of the 0.90 boundary—which makes the result look a lot more robust.

Another odd change is that while in the preprint, when doing the intention-to-treat analysis they removed 11 patients from each group, in the final paper they only removed one patient from fluvoxamine, and four from placebo. While this does make the ITT analysis look marginally worse for fluvoxamine, it also does tighten up the RR interval, which is better for it. Not sure what is going on here, maybe there is an explanation.

Coming back to the 23 extra placebo patients, they also make most of the secondary outcomes look better. I've placed the two tables next to each other for easy comparison. Does this mean this was the motive? I don't know. It may be something else. Or it may be an accident. But this is the effect the extra patients had.

So What’s the Deal With Fluvoxamine?

I really don’t know. We recently learned that the FDA refused the fluvoxamine EUA for reasons that will not be surprising to readers of this Substack. They considered the endpoint unreliable, among other issues they had with the trial. Does this mean that they are unbiased towards this drug? Absolutely not. But their points were valid. I myself am noticing that the effects of fluvoxamine in RCTs are mostly limited to women, but I know many doctors I respect are supporting the drug and its administration.

What is certain is that fluvoxamine has been used as a wedge in the early treatment world, with some people claiming that fluvoxamine was being overlooked because of the excess of the ivermectin proponents. I hope now that it has been examined and rejected, we can all get back to the real conversation, which is to examine why all generics seem to be getting rejected, with various rationales, ranging from reasonable to insane.

I will continue to examine the data on fluvoxamine and discussing what I see, especially now that the EUA is behind us and I can’t be accused of sabotaging a promising early treatment drug. We’ll see what we see.

Award-Winning Muddle

Having failed to accomplish anything positive, but putting another nail in the coffin of ivermectin, TOGETHER was just awarded "clinical trial of the year.” I suppose it depends on your criteria for what makes a winning trial.

In case you've missed my prior work on the TOGETHER trial, this is a good starting point:

This article is part of a series on the TOGETHER trial. More articles from this series here.

I haven't really looked at Ivermectin because everyone else was, and it just seemed like a good way to jump into a pit of snakes.

I did cover Fluvoxamine, and Fluvoxamine has many different MoAs from lysosomotropism similar to Hydroxychloroquine and to reducing ER Stress by serving as a sigma-1 agonist.

https://moderndiscontent.substack.com/p/the-fluvoxamine-anthology-series?s=w

It has many of the hallmarks of Ivermectin: cheap, widely available (SSRI), etc. However, it is not without some side effects. I think our culture is becoming more conscientious of things that alter mental function and with all of this talk about mass shooters I wouldn't be surprised if these concepts are related.

Why does it relate to Fluvoxamine? One of the Columbine shooters was found to have been on Fluvoxamine and so the manufacturer fell under a lot of heat and there was national outcry. I think at a time where people are both concerned about mass shootings and the mental health of our nation I suppose that could (note, COULD) be a big factor in a mass administration of an SSRI?

Or, it could really just be the old adage: don't ascribe to malice that which can be explained through incompetency.

I think it could very well be that these trials, and really many of the trials we are seeing, are just suffering from poor methodology and having many people examine these trials with a magnifying glass may really just be picking up on these errors.

Thank you for all of your hard work. It is much appreciated. I was thinking the other day that the results of clinical trials should be transparent and written for the average patient to read. In other words, it should be easy to determine the particular patient (age/sex/comorbidity) for which a drug's benefits outweigh the risks. Critical information shouldn't be buried in a paragraph or in an appendix. Perhaps a change similar to that of mortgage closing documents in the Obama era.

Also, clinical trials should be run by independent companies and trial design should be heavily scrutinized and agreed to beforehand with valuable societal endpoints (i.e. not Covid vaccine endpoints), and with regular monitoring for compliance with design.