Scott Alexander's Correction on Ivermectin, and its Meaning for the Rationalist Project

This Substack was started to host my response to Scott Alexander’s article on ivermectin. This is an update on that conversation.

Without Further Ado

Scott’s update is small and utilitarian, added to the mistakes page and the original article, about two-thirds of the way through:

UPDATE 5/31/22: A reader writes in to tell me that the t-test I used above is overly simplistic. A Dersimonian-Laird test is more appropriate for meta-analysis, and would have given 0.03 and 0.005 on the first and second analysis, where I got 0.15 and 0.04. This significantly strengthens the apparent benefit of ivermectin from ‘debatable’ to ‘clear.’ I discuss some reasons below why I am not convinced by this apparent benefit.

Well, the reader he refers to is me.

Some of you have enough context to put together the significance of what these words mean. For the rest, let’s unpack what happened:

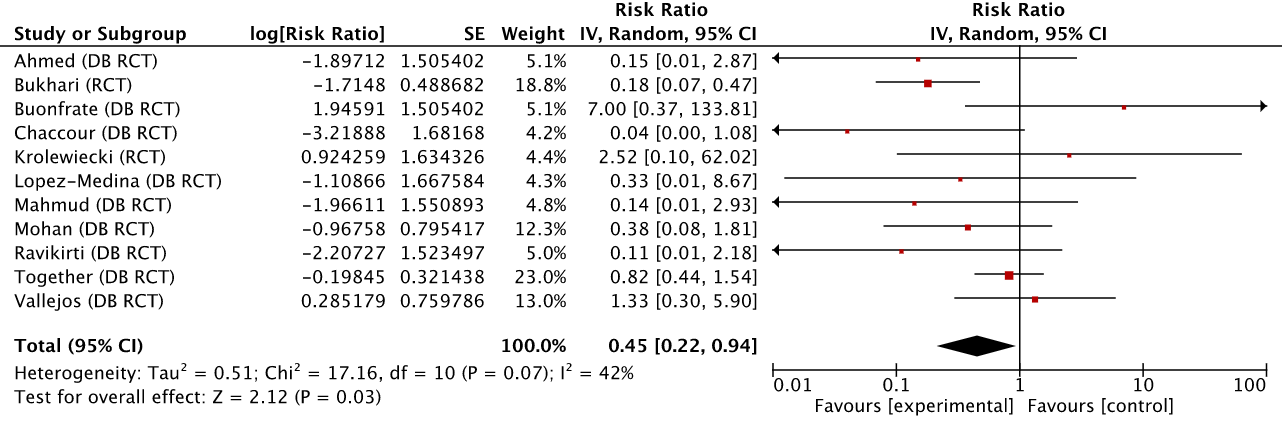

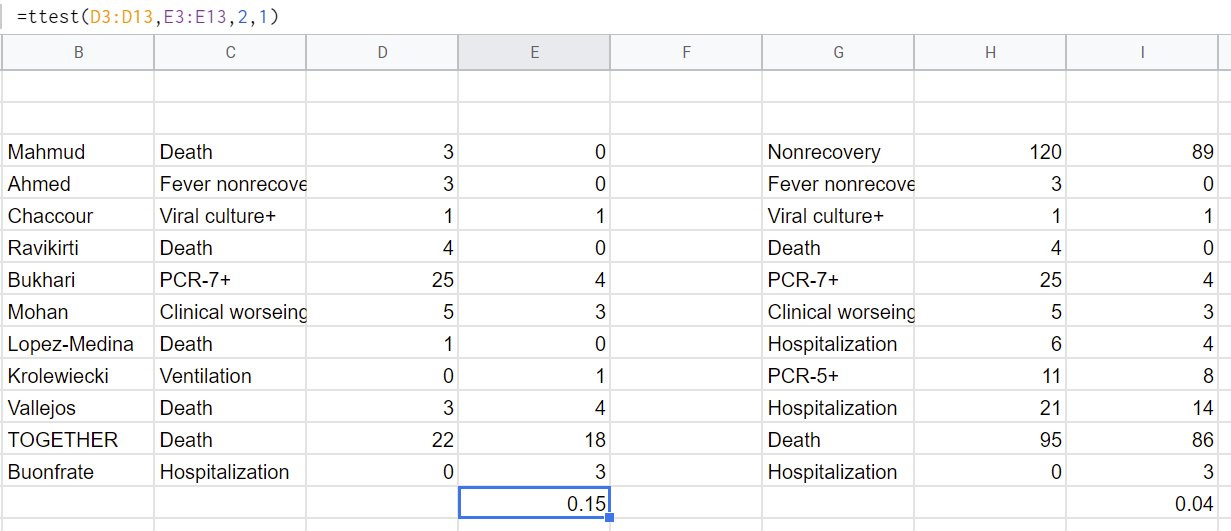

In the original article, Scott spent the first two-thirds of the text going through individual early treatment studies he found on ivmmeta.com one by one, keeping only the ones he found credible. He then removed a further six studies on the say-so of Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, leaving him with a final set of 11 studies. Of these, he attempted a rudimentary meta-analysis, from which he got a p-value of 0.15. After tweaking the endpoints in an attempt to be more fair, he got a p-value of 0.04.

For those of you not educated in frequentist statistics such as those used in most medical research, the p-values are almost always evaluated against a threshold of 0.05. Results smaller than this threshold are considered “real,” and you may have heard them be described as “statistically significant.” Results above this threshold are considered “noise,” and you may hear them described as “null,” or “negative,” or “no effect.” None of these characterizations are particularly well-justified, (and some of them are plainly wrong) but this is how medical research is communicated these days, and Scott follows this convention.

He described—and still describes—his results this way:

So we are stuck somewhere between “nonsignificant trend in favor” and “maybe-significant trend in favor, after throwing out some best practices.”

In my original article, I had re-computed his first analysis (for which he found p=0.15) using the kind of software commonly used for meta-analyses, and the result was p=0.03. In other words, I had shown that his original analysis was “significant” even though he had calculated it was not.

I should clarify here that while meta-analysis is no more my field than it is Scott’s, I’ve sought help from people who have a deep background in that world.

My response to Scott gently noted that there was something wrong here, but since I imagined that he would read my article closely and respond in detail, I chose to say no more than what he’d need to spot the issue. Rookie error, I now know:

I’m not sure how Scott ended up with a P<0.15 but the difference is large enough to make me suspect a mathematical error somewhere.

Scott’s partial response was such that it gave me the impression he understood the issue, though his lack of correction has concerned me ever since. A recent Twitter exchange made me realize that he had not, in fact, realized the error. So I went back to the original finding to understand what happened. I started with replicating his findings:

As you can see his results of 0.15 and 0.04 are replicable by a simple t-test. However, a t-test, while often used to test statistical significance in a set of primary data points, is improper for a meta-analysis. Among other things, it doesn’t weigh the different studies differently by size. Suffice to say, when someone says they did a “meta-analysis,” the process to combine the results of the individual studies to an aggregate is never a t-test. This explains why I got a much stronger signal when using Cochrane’s RevMan, which, when random effects are warranted, performs a DerSimonian-Laird meta-analysis.

[Update: some readers have been asking if DerSinomian-Laird is really an appropriate way to do this. If this is not you, feel free to skip to the end of the italicized section. This is somewhat of a red herring, as the primary question is: “is a t-test appropriate here?” and I have seen nothing to suggest it is, nor do I expect to, because it ignores a lot of relevant information.

However, let’s follow the red herring for a bit. Without getting into the depths of statistical topics, we can put it this way: It’s what everyone uses. From Tess Lawrie’s team to Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz (and again) to Cochrane to Andrew Hill to Ivmmeta. As the Wikipedia article on meta-analysis puts it:

The most widely used method to estimate between studies variance (REVC) is the DerSimonian-Laird (DL) approach.[43] Several advanced iterative (and computationally expensive) techniques for computing the between studies variance exist (such as maximum likelihood, profile likelihood and restricted maximum likelihood methods)

However, a comparison between these advanced methods and the DL method of computing the between studies variance demonstrated that there is little to gain and DL is quite adequate in most scenarios.[47][48]

I hope this is enough to resolve the “DerSimonian or t-test?” issue that seems to be cropping up]

Continuing with our story, in the process of understanding what happened, I sent a tip to the nice people at ivmmeta through the textbox on their page—I do not have another contact—who replicated Scott’s second analysis. Here’s what they had to say:

Update: after exclusions chosen by SSC, exclusions by GMK, excluding all late treatment, and excluding all prophylaxis studies, SSC found the results in Figure 29, showing statistically significant efficacy of ivermectin with p = 0.04. The method for computing this p value is not specified. We used the same event results and performed random-effects inverse variance DerSimonian and Laird meta-analysis as shown in Figure 30, finding much higher significance with p = 0.005.

While they state some objections to the particular endpoint selections Scott made, they replicated Scott’s second analysis faithfully, and found a p-value of 0.0046 (instead of Scott’s 0.04). Remember—a lower p-value means the signal of ivermectin efficacy is stronger.

And just so we don’t focus on p-values alone, Scott’s first analysis found a 55% effectiveness (RR = 0.45) for ivermectin, while the second one—while far more strongly significant—found 29% effectiveness (RR = 0.71). Clearly the choice of endpoints between the two analyses trades significance for effect.

To summarize, Scott’s own analysis—with his own choice of studies to include—and even with Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, a notorious ivermectin adversary, removing a third of the remaining studies—all of them more or less positive—a meta-analysis over the remaining studies showed a statistically significant effect for ivermectin, no matter how we slice it.

This isn’t the argument I like. This isn’t the argument I chose. I am simply correcting Scott’s argument and showing you the results of his analysis.

Had Scott not made the error he did, using a simple formula that is not suitable for meta-analysis, he would have seen these results at the time of his original piece. The error incinerated the vast majority of the evidence he so painstakingly collected.

It should be noted that Scott was highly confident that the TOGETHER trial would be high-quality, and included it in his analyses before the paper was out, even though many others were rejected on the basis of flaws discovered with the published papers. We now know that the published study may be one of the worst ivermectin studies to see the light of day.

The Bitter Pill

When talking over email, it became apparent that Scott was willing to recognize the error in a minimal way, but he didn’t feel it would change his conclusion, which it appears it did not. Here’s a shortened version of what I responded to him with:

In your article, every time you mention the 0.04 result, you couch it in doubt: "unprincipled,” "throwing out best practices,” "too few studies left to have enough statistical significance.”

Here’s one quote:

“Now it’s p = 0.04, seemingly significant, but I had to make some unprincipled decisions to get there. I don’t think I specifically replaced negative findings with positive ones, but I can’t prove that even to myself, let alone to you.

So we are stuck somewhere between ‘nonsignificant trend in favor’ and ‘maybe-significant trend in favor,’ after throwing out some best practices.”

I think this basically agrees with my analyses above—the trends really are in ivermectin’s favor, but once you eliminate all the questionable studies there are too few studies left to have enough statistical power to reach significance.”

Here’s another:

”This is one of the toughest questions in medicine. It comes up again and again. You have some drug. You read some studies. Again and again, more people are surviving (or avoiding complications) when they get the drug. It’s a pattern strong enough to common-sensically notice. But there isn’t an undeniable, unbreachable fortress of evidence. The drug is really safe and doesn’t have a lot of side effects. So do you give it to your patients? Do you take it yourself?”

None of the above make sense once you correct the result of the analyses, and these quotes form the bridge to the worms explanation.

Sidebar: As a sanity check for myself, I separated the final 11 studies you kept, based on being above or below the average (8.1%) prevalence of Strongyloides (all data from the main reference Bitterman uses in his paper). Here's what it showed:

5 Low prevalence studies: RR 0.64 [0.13, 3.10] p=0.58

6 High prevalence studies: RR 0.61 [0.35, 1.05] p=0.07I hope I don't regret sharing this, my intent is not to make some big definitive point. I'm just sharing it as an interesting indication that for the results of your analysis, Strongyloides doesn't seem to be the obvious explanation. Feel free to ignore this point if you don't find it useful.

It seems to me that you may be perceiving my actions as an attempt to score a win at your expense. I would go quite far to somehow make the end of this story not be "egg on your face.” It genuinely distresses me to be the person writing this email. I offered to start a dialogue so that the conclusion would be something far more interesting and valuable than point-scoring and narrative warfare. I wish I could turn back time and have this discussion with you before the original article was published so we could be on a different timeline. What I can do now is say that there is a preventable, possibly worse error ahead of us, which is to not update properly after discovering that the vast majority of the evidence you gathered got accidentally dropped in the last step.

In your vitamin D article, you decry the advocates for fighting a rear-guard action against the truth: sticking with a storyline that they adopted based on early flawed studies, even though better studies later disproved them. It sounds very similar to the dilemma you're facing: the worms explanation is described as relying on the faintness of the effect you found. Upon learning that the effect you discovered was not actually faint, it should be surprising to end up concluding the same explanation applies. And even if you did, I would imagine that would require new connective tissue to get there. If you think the vitamin D advocates should let their beliefs halt, melt, and catch fire upon finding their case was flawed, then you may be looking at a chance to demonstrate what they should have done instead.

In closing, please go ahead and confirm the error if you haven't already. I do think it unfortunately compromises the rest of the analysis as written and the appropriate response is to actively inform its past and future readers of this, given the impact the piece had. Where we go from there is up to you. You can remember this as a story where a conspiracy theorist got lucky and noticed something important, forcing you to lose face, or as a story where an unfortunate error became the beginning of a quest to figure out why nobody else in the multitudes that read it and endorsed it was surprised enough to retrace the steps and notice something as critical as this or point it out.

thanks for hearing me out,

Alexandros

As you have probably have gathered, Scott didn’t do what I am pretty sure most of his readers would expect, given the significance his article had in the broader conversation: correct the error as visibly as possible, attempting to reach as many of the original readers as possible. Perhaps he plans to, but after a month, I must assume the correction in the original is all we’re going to see. Maybe a note in an open thread? My disappointment cannot be overstated.

On some level, I understand the cognitive dissonance of having to correct perhaps your most popular article ever (hell, it even made it to The Economist the next day). It might have been read by millions. Even posting this correction must have been painful as hell, and nobody can force Scott to write a proper update article, explaining what happened, and coming fully to terms with the implications of his recomputation of the significance of his own findings. But without proper recalibration, the same thing will happen again.

As Eliezer Yudkowsky wrote in The Importance of Saying “Oops”:

Defending their pride in this passing moment, they ensure they will again make the same mistake, and again need to defend their pride.

Better to swallow the entire bitter pill in one terrible gulp.

Are We Rationalists Still a Thing?

On the other hand though, rationalists (I assume Scott still counts himself part of this community, as do I) are bound by a much higher standard of truth-seeking. Here are some choice quotes from an early document many of us used as a blueprint—Twelve Virtues Of Rationality:

There is a time to confess your ignorance and a time to relinquish your ignorance. The second virtue is relinquishment. P. C. Hodgell said, “That which can be destroyed by the truth should be.” Do not flinch from experiences that might destroy your beliefs.

Let the winds of evidence blow you about as though you are a leaf, with no direction of your own. Beware lest you fight a rearguard retreat against the evidence, grudgingly conceding each foot of ground only when forced, feeling cheated.

One who wishes to believe says, “Does the evidence permit me to believe?” One who wishes to disbelieve asks, “Does the evidence force me to believe?” Beware, lest you place huge burdens of proof only on propositions you dislike, and then defend yourself by saying, “But it is good to be skeptical.”

I could go on, but you get the point. The rationalist community came together over a shared desire to seek truth, and to use its superior collective capabilities to prevent existential risks. Scott is probably one of the five most prominent voices hailing from that community, and sadly, in this case, he seems to be breaking the most core of principles. He made the mathematical correction, but the remaining text is now free-floating, completely incongruent with his own results. Also, people who read the original continue to operate under a grave misapprehension about what that article found; for many, it was a definitive answer to the question of ivermectin.

Sadly, the rationalist community’s biggest contribution to pandemic discourse was to assist in shutting down a promising treatment and give a talking point to curious onlookers everywhere:

Scott Alexander and the Failures of Rationality

The erroneous meta-analysis is simply one step in a long walk of errors that got us here. These kinds of errors happen to all of us. But the reason Scott stopped at the result he got, I suspect, is that this is the result he was expecting, based on what he was hearing. It was a result that confirmed his biases. I’ve made the same error in recent memory, and I’m not sure how it can be avoided.

However, rationalists a have a toolkit with many layers of defense that should prevent such errors in several other steps along the way. Here are some steps Scott could have (arguably, should have) taken.

Step 1: Update Your Beliefs as New Information Comes In

In a follow-up piece, Bounded Distrust, Scott wrote the following:

Last year I explained why I didn't believe ivermectin worked for COVID. In a subsequent discussion with Alexandros Marinos, I think we agreed on something like:

1. If you just look at the headline results of ivermectin studies, it works.

2. If you just do a purely mechanical analysis of the ivermectin studies, e.g. the usual meta-analytic methods, it works.

3. If you try to apply things like human scrutiny and priors and intuition to the literature, this is obviously really subjective, but according to the experts who ought to be the best at doing this kind of thing, it doesn't work.

4. But experts are sometimes biased.

5. F@#k.In the end, I stuck with my belief that ivermectin probably didn’t work, and Alexandros stuck with his belief that it probably did.

It’s plausible that this is how he saw the state of the evidence on ivermectin at the time. After all, in the time between his original piece on ivermectin and the follow-up in “Bounded Distrust,” he had written a piece supporting the use of fluvoxamine, mostly on the strength of the TOGETHER trial.

And yet, the FDA has now considered and rejected Fluvoxamine, citing many of the same issues I had raised about the TOGETHER trial. Either the FDA and I are in cahoots, or perhaps we saw something Scott and Gideon did not: the TOGETHER trial was a mess.

Here’s what the NIH dashboard on fluvoxamine has to say about TOGETHER:

And yet, having seen all of that and had a massive additional lump of data that he himself collected land on his lap, Scott still seems to stand by his original conclusion on ivermectin, even though he presumably now disagrees with “the experts” on fluvoxamine. Or, if he changed his mind and does agree with them, he must also agree that the TOGETHER trial, which was a big pillar of his original ivermectin thesis, is quite simply not what it was made out to be. But that should shift him in favor of ivermectin, surely. Sadly, none of this has happened. To my knowledge, Scott retains his prior beliefs about early treatments, regardless of what the experts do or do not say.

Since that article was written, we’ve seen fraud detective Kyle Sheldrick—who Scott praised in his original piece—make absurd allegations of fraud, betraying statistical confusion and then taking down the page in his blog that made those allegations, as well as taking his Twitter profile private.

We’ve also seen Andrew Hill, who’s retraction of a meta-analysis Scott praised for updating with the evidence of fraud, be caught confessing on newly-released video that the original conclusion of his meta-analysis was improperly dictated by his sponsor—straight-up academic misconduct—at the expense of ivermectin’s adoption.

If I told you that Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, Kyle Sheldrick, several TOGETHER authors, and Andrew Hill, have also become academic collaborators, with possible conflicts of interest, and strange silences with regard to transparency of data from their studies, would you believe me?

And yet none of this seems to have shifted Scott’s evaluation of the evidence at all.

You might say he didn’t know some of this, and I can’t know for sure what he knows, but he turned down access to all this information and orders of magnitude more when he refused to even entertain a conversation, so it must count somehow.

Step 2: Don’t Remove Yourself From the Argument

Another quote from the Twelve Virtues of Rationality is:

“Those who smile wisely and say, ‘I will not argue,’ remove themselves from help and withdraw from the communal effort. In argument, strive for exact honesty, for the sake of others and also yourself: the part of yourself that distorts what you say to others also distorts your own thoughts.”

Both now and when the original piece came out, I practically begged Scott to engage in conversation with me. The things I needed to convey were so many that if I wanted to go through them all, I would need to send him a tome, not an email. Without him agreeing to discuss, it would be a tome nobody will read.

For instance,

Scott writes that once Elgazzar is removed, “A lot of the apparent benefit of ivermectin in meta-analyses disappeared.” This is simply not true, but is a factoid that Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz was circulating.

He also makes a few mistakes with reading certain studies: In Buonfrate he seems to misunderstand that the values he is comparing are logarithms. He also seems to miss the fact that the two Ahmed ivermectin arms have drastically different doses.

Likewise, Scott seems unaware that several highly publicized studies—like TOGETHER and Lopez-Medina—that show weak (if positive) results have backstories of controversy that are not dissimilar to many of the studies he threw away. Ivmmeta did not make its own commentary, it simply aggregates what is done by the wider community. Obviously, these two studies have received much more attention than some of the tiny ones.

Scott writes that Jack Lawrence is a “medical student.” He’s actually a former journalist and “disinformation researcher” currently pursuing a Masters’ degree in Biomedical Sciences.

While he says he has “immense contempt for ivmmeta,” for criticizing TOGETHER (the largest RCT on ivermectin), while leaving much smaller and more flawed studies without comment, he doesn’t seem to notice that Meyerowitz-Katz has a worse version of the same bias. While he had said that not sharing data is a “red flag” for studies, TOGETHER has not shared raw data for two months after release now—despite promises to the contrary—and yet Meyerowitz-Katz and his companions are busy defending the trial instead of pounding the table for data.

These are a few errors that spring to mind, but there are many throughout the text. They all reflect distortions coming from exclusively, if critically, processing information coming from one side of the debate.

Scott’s refusal to even enter a discussion ensured he was “not convinced by this apparent benefit” that he found for ivermectin, since correcting just one unambiguous error took me over a month of back and forth with emails that took quite a long time to write—time I didn’t have. Without Scott deciding to become curious about what’s *actually* happening of his own volition, there’s nothing more I can do within a reasonable timeframe.

Step 3: Beware Isolated Demands for Rigor

Despite analyzing positive studies quite deeply for errors, and even dismissing some of them on the say-so of a known ivermectin opponent, he accepted the “Worms!” analysis based on a series of Tweets.

My original response recommended caution:

The worms hypothesis should be studied, but we are nowhere near far enough in the process to be elevating it into any sort of definitive explanation for anything.

The study is now published, and, as I expected, critical flaws have become apparent. The most important for me, is that Bitterman’s paper mixes and matches datasources improperly to get to its result, in a pattern highly indicative of cherrypicking.

To explain what I mean, Bitterman’s paper in JAMA divides the world into just two categories of “high” and “low” Strongyloides prevalence, with the average prevalence coming from his main data source. And yet, only for Brazil, a different datasource is used. The one used for Brazil uses a different method for estimating prevalence of Strongyloides, which is not adjusted when compared to the other data. If adjusted, it would significantly diminish or eliminate the correlation found. The Brazil-only datasource also estimates Strongyloides presence for a historical period (versus a present projection as the main source does). And while the paper tries to excuse using a special datasource only for Brazil by saying that they used higher granularity data where available, it seems they could not find the numerous studies that offered higher granularity data for other countries (e.g. Argentina). In other words, all signs point to a forced outcome that was willed into existence rather than a natural conclusion of the data when looked at dispassionately.

To quote Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, “Should we publish every correlation during the COVID-19 pandemic?”—especially spurious or tortured ones with myriad confounders, like the one relating to worms, ivermectin, and COVID. I mean, why not just make another one up about toxoplasmosis, COVID, and ivermectin? Yes, the papers are there if you look. I suspect the same analysis can be done for most other parasites.

And yet Scott’s piece pointing at Strongyloides was influential enough to get pundits on national media feeling certain they knew what the story of ivermectin was:

Step 4: State Your True Objection. Don’t Use Arguments as Soldiers

I engaged Scott’s article because I felt that he had laid out his case openly, in a way that I could pinpoint the errors so that we both could improve our understanding. And yet, when I pointed out that the vast majority of evidence collected had been scattered to the wind, nothing seemed to change with the analysis: not even his estimated probability of 85-90% moved. Did Scott truly describe the reason he thought ivermectin didn’t work? Or did I waste my time operating under false pretenses?

This wasn’t the only instance. In his original piece he wrote:

Not only would a recommendation to trust experts be misleading, I don’t even think you could make it work. People would notice how often the experts were wrong, and your public awareness campaign would come to naught.

And yet, in “Bounded Distrust,” having at least in part digested that the meta-analysis argument is not as strong as he thought, he switched this around:

In the end, I stuck with my belief that ivermectin probably didn’t work, and Alexandros stuck with his belief that it probably did. I stuck with the opinion that it’s possible to extract non-zero useful information from the pronouncements of experts by knowing the rules of the lying-to-people game. There are times when experts and the establishment lie, but it’s not all the time. FOX will sometimes present news in a biased or misleading way, but they won’t make up news events that never happen. Experts will sometimes prevent studies they don’t like from happening, but they’re much less likely to flatly assert a clear specific fact which isn’t true.

I think some people are able to figure out these rules and feel comfortable with them, and other people can’t and end up as conspiracy theorists.

Many friends (and some who don’t like me very much) interpreted this passage the same way: as Scott calling me a “conspiracy theorist.” Please don’t feel bad for me, I’ve heard much worse, and this isn’t why I included this—it’s all part of the game we’re in. The reason this is here is because Scott justifies this characterization in part based on his belief stated elsewhere in that article that “experts aren’t quite biased enough to sign a transparently false statement—even when other elites will push that statement through other means.”

It’s hard for me to convey the overwhelming irony of pointing a statement like that in my direction, if only because I am the person who discovered that the authors of the infamous February, 2020 Lancet letter—decrying the lab leak hypothesis as a conspiracy theory—was signed by experts who claimed to have no conflicts of interest, while at the same time most of them were affiliated with institutions that had a lot to lose if the lab leak hypothesis became accepted as truth. In fact, it later turned out, that many of them had collaborated on a proposal to do exactly the kind of research that could create this kind of virus.

And for more examples of the same motif, look at the John Snow memorandum, stating unambiguously that “there is no evidence for lasting protective immunity to SARS-CoV-2 following natural infection,” months after the evidence had started to flood in. I can keep going. Yes, bonafide experts have signed their names under many false statements in the last few years alone.

Step 5: See Through the Eyes of the AI

There’s something about the constant subtle jabs at ivmmeta in Scott’s original piece that really gets to me. For instance, his piece still contains the following:

(how come I’m finding a bunch of things on the edge of significance, but the original ivmmeta site found a lot of extremely significant things? Because they combined ratios, such that “one death in placebo, zero in ivermectin” looked like a nigh-infinite benefit for ivermectin, whereas I’m combining raw numbers. Possibly my way is statistically illegitimate for some reason, but I’m just trying to get a rough estimate of how convinced to be)

This paragraph now makes no sense of course, since his results are actually acknowledged to be much stronger than when it was written. Perhaps this observation should have been a warning that something wasn’t right at the time it was being written.

But what truly bothers me is that Scott denigrates something we’d expect every sane civilization that is hit with a novel disease to do: keep a public, live, meta-analysis tracking every single study on 42 different proposed treatments, and an even broader list of 837 proposed treatments for the disease, constantly updating with every scrap of evidence it can find anywhere, in favor or against any of these. Instead of providing feedback for how to do the job better, the message Scott seems to give is “give up, leave this up to the journals and the fraud detectives.”

I understand the concern Scott may have about ivmmeta being biased, but whenever I’ve found an error, I’ve always used the textbox on the website, and the error has been fixed within a day or two. Say what you want about them, these people have built a formidable ark of scientific knowledge, and they’re humble enough to fix their errors immediately. They don’t pretend to be perfect, but they are open to suggestions, which is why the rationalist project should embrace them as doing the obviously correct move: gathering evidence from all corners, and combining it the best they can. Instead, we’ve labeled them partisan and abandoned them to the wolves. Sad commentary on the state of our sensemaking as a species.

Step 6: Semi-Permeable Membranes

One thing that shocked me was how hard it was to discuss even a simple thing with Scott, even when he knew I could have made a big deal about this without giving him an opportunity to make whatever correction he thought appropriate. It felt like communicating through a straw. I get the sense that Scott is busy. Busy and/or surrounded by people who think the world of him; a community of readers that compliment his writing early and often.

Yes, he has those who can’t stand him, but it’s unclear how much he interacts with them. (By the way, his haters had to concede that despite their seething disdain for Scott, his ivermectin piece was very good. I have no words.)

As a result, my sense is that Scott has full intellectual freedom (good!) but nobody to challenge him when he releases something weak. No loyal opposition.

Rationalists! This is not a drill—we are failing our own at perhaps the most important thing this community was supposed to be about: holding each other to a higher standard than we hold people outside the community. Helping each other overcome our biases. If the rationalist community is more about the rationality aspect (outthinking the world to save the world) than it is about the community aspect (a group of friends who will support each other no matter what), then this realization should raise an alarm. One of us, one of the biggest contributors to our body of knowledge, has veered so far out that he has failed at most of the 12 virtues of rationality, by my count. How did it get to this? What’s the value of the incremental malaria net when we collectively failed to help humanity make sense of the sudden onset existential risk called “the pandemic” (especially when governmental reaction is taken into account)? Have we become too well-fed and comfortable with our lot in life, putting the whole light cone at risk?

No More Binding Our Wings

The "Bounded Distrust" essay's main point is that an astute analyst can extract useful information from expert pronouncements, even if one understands them to be sometimes deceptively worded, and still maintain their broad trust in the system. Failing to do that leads one astray.

The problem with bounded distrust is its corollary: unbounded trust. In order to apply the principle, one must assume the system is fundamentally sound. I made that mistake once too, but I am Greek: I've seen a trusted system go down in flames in my lifetime already, and I’m starting to spot a pattern.

Scott was, and to an extent still is, one of the people I respect the most for the insights they’ve given us, and many of the people I look up to respect him greatly, too. The self-preserving move here is to say nothing. But this is not about me. And it’s not about Scott. It’s about events that have had an impact on the world. Millions of lives have been lost in the pandemic, and things do not appear to be getting any simpler as we head deeper into this decade. If I can’t articulate a point this important clearly, for fear of displeasing the big names of the community, then there is no such thing as a rationalist community. Just another community like all the others, but more dangerous, because it doesn’t realize that’s what it is.

Speaking as a rationalist still, we have to look beyond individuals, and decide what standards we want for our community, and what are the clear red lines that call for breaking through bystander apathy and doing something. If the current rationalist clustering has lost the ability to follow the evidence wherever it leads, perhaps we need to start over. My sense is that things will not get any easier where we’re going, and we need to get ourselves in top shape.

Each individual in the rationalist community has two choices coming out of this experience: we can sacrifice the meaning of rationalism and fall into line behind names we trust, or we can take this opportunity to learn how this mistake progressed through our internal checks and balances as far as it did, and get better.

Scott (and the other rationalists with large platforms) face the same choice as we all do. For those who choose to circle the wagons, there are many examples of how to build a group and protect it from challenge. But rationalists who choose to learn from this event have a much more appropriate toolkit to draw on, and a new, personal example of how easy it is to go down the wrong path in the pursuit of truth.

The rationalist community has built an incredible war chest of tools, heuristics, terminology, and dissolved problems to help us see clearly what’s around us. I do not intend to give up any of it. We do need to find out what is missing though, so we can develop a 2.0 version, suitable for the challenges ahead.

My Twitter DMs are open if anyone wants to reach out privately, and of course I’ll be reading the comments below. If you want to continue following the state of the conversation as it develops, consider subscribing to this Substack. It costs nothing but your time and (inbox) space.

Ah, you kids.

Take it from me. No matter what you call yourselves--what philosophical school you wish to adhere to--human nature is human nature. We believe what we believe with a passion that surpasseth all passion until we stop believing it and believe something else, and then we can't believe we ever believed the former, having now become wise.

He prides himself on his intellect; he's had some battering done to him in the past and all his wounds are still raw; he wants to be loved again by the arbiters of popular acceptance. If he joins the side of the lepers his life's work is lost.

You pride yourself on your reasonableness; you've followed this ivermectin trail openly, inviting collaborators globally to join in the quest for truth; it's really painful to be treated contemptuously under Scott's guise of rationality and superior intellectual capacity.

Don't ache over it. You've done good and honest work and those of honest temperament see it, are glad of it, and hold for you the only sort of regard that matters.

Scott is, perhaps, not as towering a philosopher as popular rumor would have you think.

Thanks for the reasoned and passionate essay, Mr Marinos. Too bad Semmelweis didn’t have benefit of peers with your dedication to rational methods and discourse. Perhaps he could have avoided the asylum. Thanks also for the recent article on Dr. Malone, re inventor claims.

(Btw, I’m disappointed that you don’t seem to have a larger audience. The small number of likes for your articles is a little depressing. You deserve more visibility.)